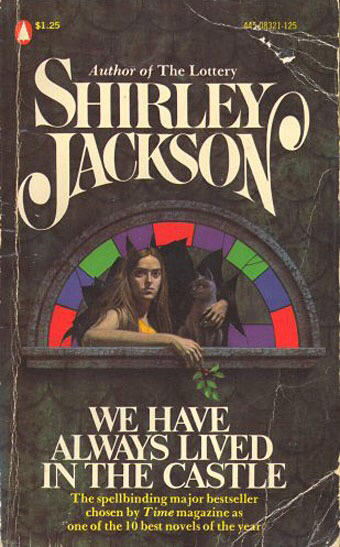

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality. For centuries women’s identities have been intricately tied to The House, and the act of homemaking – managing and creating the world within and around the home itself. Our spirits anchored to these structures of domesticity, like ghosts for all eternity. The House serves as a symbolic and literal space of confinement, of societal expectations, like a tightly laced corset, molding us into unnatural shapes, restricting our breath, until all we want to do is scream. But, we can’t because that would be...unladylike. We are all haunted houses, carrying the weight of ideals, and expectations, coupled with the past, present, and future. I am like a small creature swallowed whole by a monster, she thought, and the monster feels my tiny little movements inside. ― Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House Horror, particularly the books and stories of Shirley Jackson, validated my experience of the world and of others. The monsters are next door, they are sleeping next to us, and sometimes...they are inside us. The monsters are here. Through Jackson’s writing and the genre of horror in film and literature, I learned who I could be, outside of The House. Horror stories were the only acceptable space where women could scream, roar, rage, and resist. Stories of werewolves were all that addressed the confusing experience of puberty with its hair growth, painful shape-shifting, and growing into something altogether...monstrous, yet powerful. Like Merricat Blackwood in Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, I too thought that I could have been born a werewolf. I met Merricat when I was nine, when I came across a book cover in the library that featured a young girl with long, dark hair like mine. She was looking out of a broken window with a black cat at her side. I also had a black cat named Cornelius at the time. Prior to this I had been fortunate enough to live those short nine years in the same place with a loving, attentive family. I found myself plucked from this life and everything I knew, without warning, to live among violent, abusive strangers. Desperate to have some control over my existence and some small bit of hope to keep me going through the days, I developed OCD. Like Jackson’s Merricat, I wove magic and spells made of numbers and daily rituals to protect myself. In Merricat, I met someone as odd as myself, just when I needed it most. I no longer felt quite as helpless or alone. It was then that I learned the world is full of people and adults who would rather look away or play the voyeur when monstrous things occur. Like the girl in almost every horror film, who vehemently insists that something is not right. In fact, something is very wrong, (Don’t you see? Didn’t you hear?). My experiences, and those of countless other women, are too often disbelieved, dismissed, and disregarded, sometimes until it is too late. That is, unless you can manage to save yourself, because no one is coming to save you. Because of horror, I not only realized this, but saved myself, becoming my own Final Girl. The Final Girl trope (and much of horror), is not without its problems - still told primarily through the male gaze, the good, beautiful and virtuous survive – but, it provided me with the tools I needed to escape. To survive. To live. To act is to engage in the reality of horror - to look away, you can forget it ever happened. You can reason it away. Horror forces a mirror up to us and makes us confront things in ourselves and in our society that make us deeply uncomfortable and vulnerable. Those of us that enjoy the genre are often made to feel ashamed, or even less intelligent than our peers. To indulge openly in “taboo” subjects like sex, violence, death, and fear, is deviant. Horror reaches for ways to confront and discuss the things we refuse to - gun violence, rage, racism, police violence, grief and loss, or gender violence. Our relationship with horror is much like play for the young child, whose work is often playing house. Through playing “house” young children come to understand how to navigate the world and their place within it. For us, horror can do the same. How can we face our fears? How do we escape? What choices do we have? How do we learn to truly live? Horror has been my advisor, therapist, and healer – things I was never going to get from the mainstream offerings I was expected to enjoy like rom coms and The Babysitter’s Club. To learn what we fear is to learn who we are. Horror defies our boundaries and illuminates our souls. ― Guillermo del Toro, Haunted Castles, Dark Mirrors Today, horror and the benefits it offers us are more relevant and needed than ever. For now though, The House will continue to breed restless spirits who give birth to angry, sometimes vengeful ghosts. Some of us may struggle to break free, to move on, but The House does not let us. So we cry, and moan, and the walls creak with our rage. Haunting. Haunted. Sarah Chavez is the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, co-host of the new podcast Death in the Afternoon, and co-founder of Death & the Maiden. In addition to working as a museum curator she writes and speaks about a variety of subjects including the relationship between food and death, Mexican-American death history, and decolonizing death rituals. You can follow her on Twitter.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

September 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed